Nature's Elders

On 25 November 2021, South Australia established the biggest national park in the country and one of the biggest in the world: Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert.

Thanks to your support, together we've helped deliver the biggest national park in Australia in the Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert, protecting 3.6 million hectares of undamaged desert ecosystems.

Watch South Australia Director Peter Owen discuss the historic announcement of Australia's biggest national park.

For over a decade, the Wilderness Society has been working to protect this globally important ecosystem. Finally, on 25 November, 2021, Australia's largest ever national park in the Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert was proclaimed by the South Australian government. Covering 3.6 million hectares, it is almost four times the size of the famous Yellowstone National Park in the US. This is a grand initiative, on a scale we have been advocating from the start. It is a significant step towards a huge conservation corridor in the heart of Australia, allowing endangered animals and plants to move and adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

Spanning three states and an area almost three times the size of Tasmania, the Simpson Desert is one of the most undamaged desert ecosystems in Australia and the world, with a host of endemic plants and animals. It joins what was a bumper list of new protected areas around Australia announced over the last couple of years.

The Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert sits within the Lake Eyre Basin, alongside Queensland Channel Country and Kati Thanda / Lake Eyre, which is on the Important Wetlands in Australia list and an Important Bird Area (IBA).

Nowhere else in Australia can you see the range of colours, from brilliant white to dark red, tones of pinks to oranges, than in the desert’s extensive dune fields. Then when the rain does fall the landscape erupts in desert wildflowers, which may include billy buttons, poached egg daisies and cunningham bird flowers.

It’s one of the last great desert wilderness areas left in the world, with temperatures in summer approaching 50 degrees Celsius and large sandstorms common. It sits on top of the Great Artesian Basin, one of the largest inland freshwater drainage areas in the world.

For more than a decade the Wilderness Society has been working to protect this area, getting two fossil fuel companies to withdraw their plans to start damaging exploration work in the fragile desert environment. And now, thanks to your support, much of this precious desert ecosystem has been protected as a national park.

"This new national park is a grand initiative, on a scale we have been advocating for over a decade. Conservation measures like this are critically important, allowing endangered animals and plants to move and adapt to a rapidly changing climate." Peter Owen, Director, Wilderness Society South Australia

Despite most parts of the desert receiving 5 inches (125mm) or less rainfall annually, the Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert is home to over 900 species of flora and fauna, including the water-holding frog and a number of reptiles that inhabit the desert grasses.

Desert mammals here include the hairy-footed dunnart, crest-tailed mulgara (a small marsupial carnivores) and kowari (a brush tailed marsupial rat), while birds endemic to the desert include the grey grasswren and Eyrean grasswren, each evolved solely to survive in this exact spot.

They live alongside iconic thorny devils, budgerigars, dingoes, and wedge-tailed eagles, as well as a wealth of other flora and fauna who have learnt to adapt and thrive in these conditions. The wedge-tail eagles are known to nest near the ground, in large piles of sticks, which is rarely seen in other areas they inhabit.

The Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert is as rich in First Nations history, spanning many thousands of years, as it is in the rainbow colours of its sand dune sunsets.

The South Australian section is the traditional lands of the Wangkangurru/Yarluyandi people, other groups include Aranda and Arrente, who all maintain a strong connection with Country.

Their stories are interconnected with the landscape, such as stories of mikiri (or freshwater soaks) in the claypans, swamps and small salt lakes that enabled them to travel through the country using these for secondary sources of food and water. Rock carvings and places of cultural significance occur throughout the desert region.

There are limited roads, no buildings on the landscape and no industrial disturbance, making the Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert a rare intact ecosystem that has been the Country of First Nations people for thousands of years. As one of the last regions where nature hasn’t been disturbed by industrialisation, we need to consider how it will be protected for the future.

Is it a place we will cherish, or will we allow it to be destroyed for fossil fuels?

The Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert contains the world’s longest parallel sand dunes, held in position by vegetation. They vary in height from 3 metres in the west to around 30 metres on the eastern side. However, the largest dune, Nappanerica or Big Red, is 40 metres in height and a sight to behold. Image: Bill Doyle.

Winter is the time tourists come to popular landmarks, including the ruins and mound springs at Dalhousie Springs, Purnie Bore wetlands, Approdinna Attora Knoll and Poeppel Corner (where Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory meet). Image: A Gidgee (Acacia cambagei); Bill Doyle.

Follow in ancient footsteps exploring land few people have seen or take the Old Ghan Heritage Track through the desert on its way from Port Augusta in South Australia to Alice Springs, following the route of the original narrow gauge Ghan line.

As well as threat from climate change, the Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert is at risk from human exploration for fossil fuels, with Texan company Tri-Star currently pushing for approval from the South Australian Government to explore a number of mining leases it holds.

In 2010, the Wilderness Society South Australia travelled into the Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert to document its wilderness values. We were lucky to be there after a big rain. Every once in a while, rain transforms the swales between the sand dunes into temporary wetlands. Thousands of birds flock here from across Australia to feed and breed. Then native flowers burst into colour across the burnt orange sand, a beautiful garden that seems to stretch into infinity.

This remarkable landscape reaches for millions of hectares across the heart of Australia. It protects unbroken sand ridges and ecologically vital wetlands like Kati-Thanda / Lake Eyre. It's a sanctuary for unique plants and animals. And it's Country for First Nations people, who've been here for thousands of years.

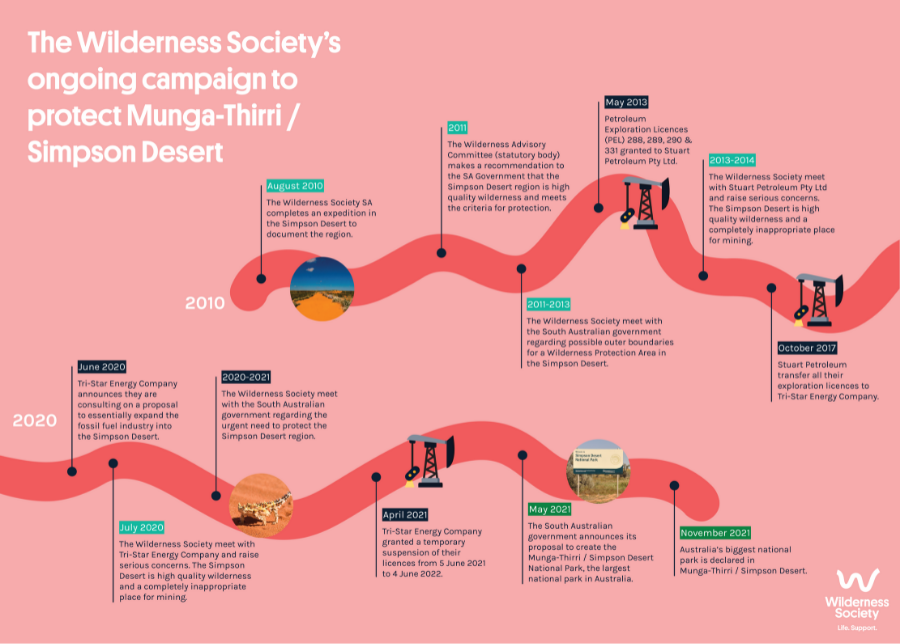

For over a decade, the Wilderness Society has been working to protect this globally important ecosystem. After our first expedition, the former South Australian government recognised the Simpson Desert as high quality wilderness. But just before the area could be officially proclaimed under the SA Wilderness Protection Act, 1992, fossil fuel exploration leases were issued across the region, essentially locking it up for the fossil fuel industry.

We were able to convince the first companies who bought the leases to pull out, making it clear the community would not stand for mining in one of the most intact desert ecosystems the world has left. Sadly, in 2017, a multinational named Tri-Star Energy Company took up the leases in the Simpson. Then in 2020, when the country was in COVID lockdown, they announced their plans for exploration.

The Wilderness Society then met with Tri-Star to express our serious concerns with their proposal, as well as relevant government officials and Ministers. We held public meetings and ran a major community awareness program, including billboards around Adelaide.

On 25 November, 2021, Australia's largest ever national park in the Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert was proclaimed by the South Australian government. Covering 3.6 million hectares, it is almost four times the size of the famous Yellowstone National Park in the US. This is a grand initiative, on a scale we have been advocating from the start. It is a significant step towards a huge conservation corridor in the heart of Australia, allowing endangered animals and plants to move and adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

But to achieve this, the expansion of the fossil fuel industry into the region must be stopped. There will be no conservation if bulldozers are able to rip through the shifting sand dunes and drill into fragile groundwater tables. They'll disrupt the desert's cycle of water and life, erode vital habitat and destroy this wilderness area forever.

Fossil fuel companies try to pitch 'exploration' as a gentler phase than production. In fact, it can be even more destructive. To find gas, they often bulldoze grid patterns across massive areas. How do you bulldoze the Simpson's sand dunes without messing up it's delicate ecology? It could fundamentally change the flow of water that brings wetlands like Lake Eyre to life. They may build roads and sink wells into precious ground water tables like the Great Artesian Basin, which supply large areas of the continent with water.

This could lead to new gas pipelines through Australia's pristine desert ecosystems, so more carbon can be burned at the other end. At a time when we need to do everything possible to keep our climate liveable, it's unconscionable. The mindless expansion of the fossil fuel industry poses a direct threat to life as we know it on this planet. Australia's deserts are on a path to becoming too hot to support life.

As climate disasters rage around the world, the United Nations chief has warned that the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report is a 'code red for humanity'. The International Energy Agency has also stated that oil and gas exploration needs to cease this year to secure a safe climate.