What are Hollow Bearing Trees (HBTs)?

Tree hollows are cavities formed in the trunk or branches of a living or dead tree. Hollows are found in older, mature trees.

They form as a result of wind breakage, lightning strikes, fire and/or from consumption and decay of internal wood by fungi and insects—primarily termites.

Where are they found?

Hollows are mostly found in old eucalypt trees, and are rare in many other native and introduced species such as wattle and pine.

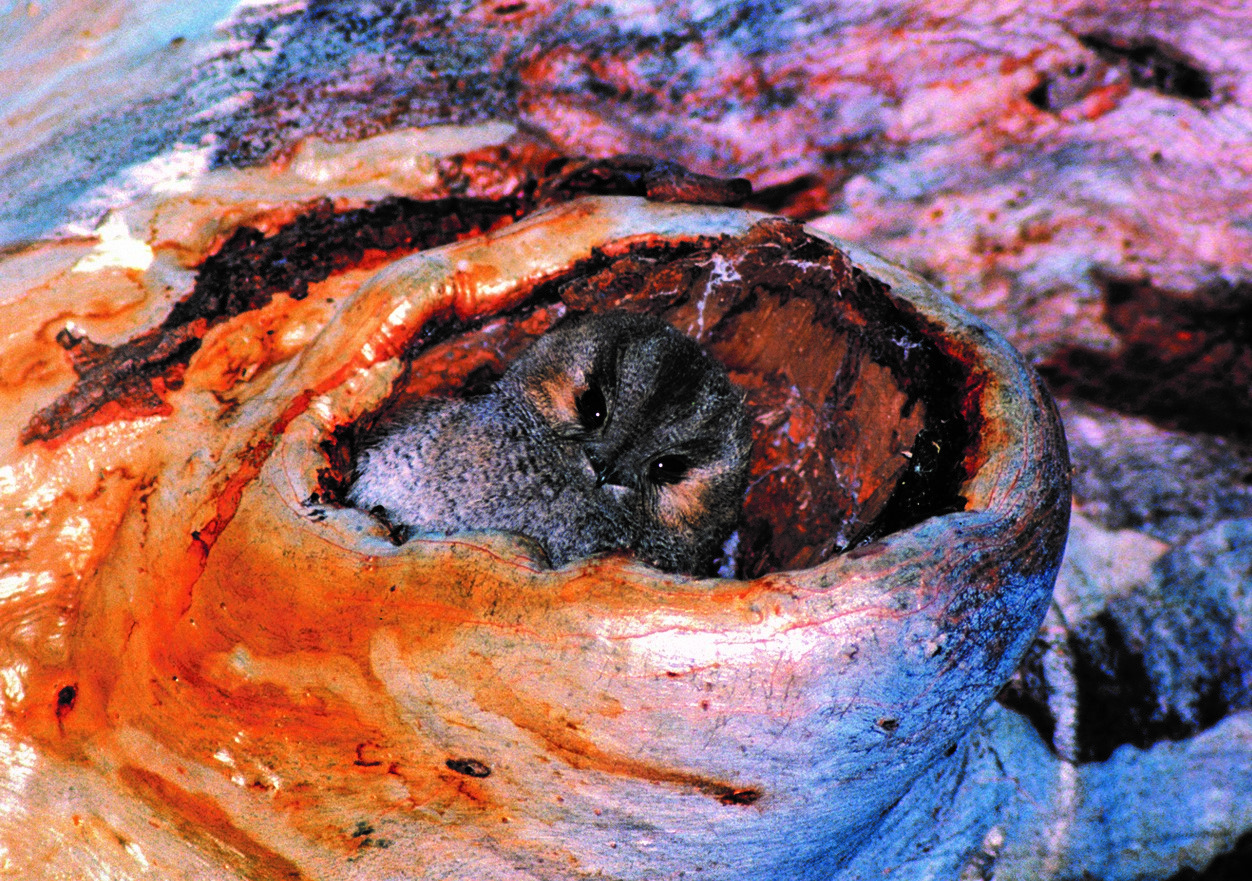

- Small hollows can take 120-150 years to form¹. Their narrow entrances are suitable for small animals, such as the Eastern Pygmy Possum

- Medium hollows can take over 200 years to form. These are favoured by animals such as Leadbeater’s Possums and Swift Parrots

- Large/deep hollows are only found in old & overmature trees (deteriorating, dying or dead). They’re occupied by Glossy Black Cockatoos and other larger animals such as Masked Owls

Large, old HBTs are generally more valuable to hollow-using animals than younger HBTs, although these are important as a future source of hollows. Very old mature trees like River Red Gums Gums, Jarrah and Marri Trees (two to three centuries in age) provide a dynamic supply of different-sized hollows that suit various species, supporting ecosystem diversity and abundance.

Who lives in them?

In Australia, 303 native wildlife species rely on hollows to nest, breed, shelter and feed¹. This includes 31% of native mammals and 15% of native birds. Each animal species has its own requirements in terms of hollow size, location (branch or trunk), tree species and surrounding vegetation, which affects how a hollow is used.

How do they help threatened species?

Many Australian native forest species rely on very specific hollow types to be able to breed and take shelter from native and introduced predators. These species are now threatened (or becoming so) because of a lack of appropriate hollows.

Threatened species or species of concern that rely on hollows to survive include:

- Swift Parrot (Critically Endangered, Tasmania—for breeding/nesting season)

- Leadbeater’s Possum (Critically Endangered, Central Highlands, Victoria)

- Superb Parrot, Powerful Owl² and Greater Glider (Vulnerable, Eastern and South-Eastern Australia)

- Carnaby’s Cockatoo (Endangered, South-West Australia)

- Yellow-bellied/Fluffy Glider (Vulnerable, Queensland and NSW)

- Western Ringtail Possum (Critically Endangered, South West WA)

What are the other benefits of old trees?

Mature trees store more carbon³ and often provide more flowers, nectar, fruit and seeds than younger trees. They also provide more diverse habitats for insect populations on their trunks and around their roots. When HBTs collapse or shed limbs, they also provide hollow logs that serve as important shelter sites for wildlife⁴.

So what’s the problem?

The primary causes of HBTs disappearing from our landscape are:

- Deforestation: HBTs of all maturity levels are bulldozed for urban development and agriculture, and those left behind frequently suffer from poor health ('dieback'), are blown over in storms, and have a shorter lifespan than in forested landscapes

- Logging: HBTs are felled and those retained can be burnt in high-intensity, post-logging fires or suffer dieback⁵

- Firewood collection or pruning: This mostly happens to overmature trees, with the removal allegedly to reduce risk to surrounding human populations

- Other human-driven changes: Changed fire regimes in northern Australia lead to high intensity, late dry season burns that kill developing and current HBTs

The biggest issue outside of direct loss of HBTs is the loss of younger and developing trees that will soon develop hollows, leading to a future lack of hollows. All factors above lead to this loss of the next generation of HBTs, but this is especially an issue in logged forests where trees of 20-80 years of age are preferred by the logging industry.

This loss and lack of recruitment of new HBTs leads to either:

a) a complete lack of hollows

b) not enough of the right type of hollows to maintain a viable population of various species, or

c) the hollows being in the wrong place (e.g. on infertile or rugged ridges) for the animals to also find food and water.

Why is this happening?

These trees are being lost because:

- State governments are legally enabling deforestation and logging, and subsidising logging, resulting in ongoing loss of HBTs

- The Federal Government is not enforcing national environment laws and recovery plans for threatened species, and has exempted logging from national environment laws under the Regional Forest Agreements in place in WA, NSW, Victoria and Tasmania

- There is no real protection for these trees and recovery plans (where they exist) can’t be enforced to stop the threats above

- Political decision-making has ensured that destruction of HBTs is not listed as a ‘key threatening process’ under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, leading to no Federal plan to end the activities killing them off

Why can’t we just replace tree hollows with artificial nests?

Some success has been had, for some species, with replacing real hollows with artificial nesting boxes—but it’s been very limited and has often failed totally. It’s also very expensive as a solution, and is no justification for continuing to destroy natural HBTs.

What’s the solution then?

The solution is to allow forests and bushland to become old. This requires an end to the destruction of current HBTs and restoration of forest and bushland to ensure a steady supply of future HBTs of varying ages and tree species. This should happen across the country, but priority should be given to critical habitat for threatened species, such as Victoria’s eastern forests, South West WA, northern and eastern Tasmania and northern NSW/south-east Queensland.

The states won’t take action on their own to end the destruction of HBTs in high conservation value (HCV) forests and bushland, so we need the Federal Government to show leadership through:

- Strong national laws that end destruction of old and high conservation value (HCV) trees, and forest management rules that protect all current and future HBTs and threatened species habitat in HCV forests

- An independent Environment Protection Authority to make sure environmental decision-making is independent, based on science and free from the influence of vested interests

- Development, resourcing and enforcement of a national plan to ensure a regular supply of HBTs in future (through a mix of protected areas and protection and restoration of HCV vegetation from native forest logging/deforestation)

- Support for Indigenous ranger and traditional fire management programs in northern Australia

Yes, I want new laws for nature!

Tens of thousands of Australians want strong national nature laws that end deforestation and an independent watchdog to enforce them.

Are you one of them?

¹Gibbons, P & Lindenmayer, D (2002) Trees hollows and wildlife conservation in Australia CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria

²Under state legislation, not listed Federally

³https://theconversation.com/bi...

⁴http://www.environment.nsw.gov...

⁵Clearfell-logged areas are more susceptible to more frequent and higher intensity wildfires